Parrot Theory 101

at Reid Hall, Columbia University Global Center, Paris

PARROT THEORY 101

The color chart, along with other indexes from the archives of Eden, is now being revisited in many artistic endeavors. Its symbolic power seems to be swinging back to the forefront of cultural production and indeed, suddenly, we are once again talking about color. But I say, we cannot talk about color without talking about parrots!

So we will take this occasion to do just that, to explore the various manifestations of parrots and colors --in contexts. In addition, we are going to speculate about the rather promiscuous relationships between language, speech, and written text. We will examine the claims of recent scientific research on parrot speech, as well as historical conceptions of language and recent theorizations of syntax. To conclude we are going to talk about the interactive realm of mirrors, focusing on their psychological and cultural applications.

COLOR

order and signification of knowledge/power

CONDITIONS OF THE SPECTRUM

1) nature > the functions of pigmentation, mimesis, camouflage, recognition

Pigmentation in the natural kingdom is a matter of molecules. Many animals display pigmentation mimicry. This can be commonly seen in nature as camouflage for protection or as warning coloration. Coloration is also employed for mating rituals to attract the attention of the other. Chameleons use pigments to blend into their surroundings by controlling the molecular absorption levels of the electromagnetic spectrum. A chameleon is capable of scanning the surroundings to determine its own pigmentation, an ultimate form of visual-chemical empathy

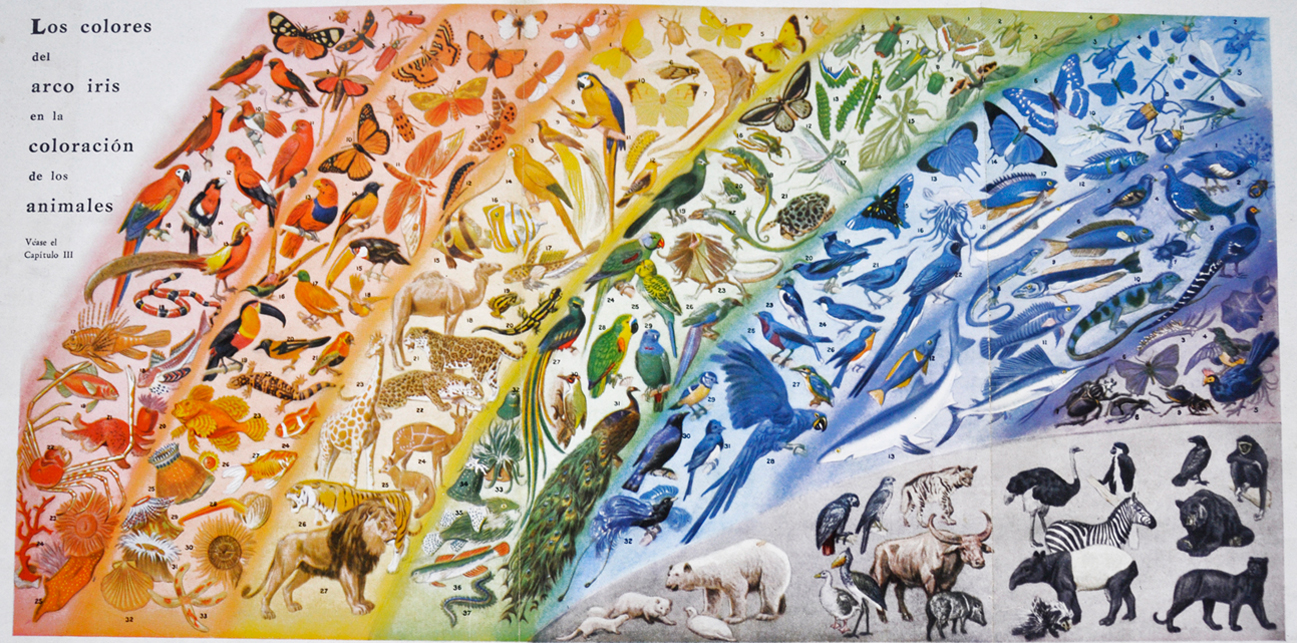

Here is an illustration I found in a natural science encyclopedia. It displays the spectrum of pigmentation in the natural kingdom. As you can see, the only animals in every color gamma are parrots. So we, like people in Amazonia, also acknowledge that parrots signify the color chart in nature.

2) myth > color as the order of nature > social hierarchy (tribal headdress)

In many tropical cultures the fact that parrots are the most pigmented species of birds was not overlooked. There existed everywhere – then as now-- ritual uses of pigmentation for the codification of social values. The chiefs and holy men of some Amazonian tribes, for example, wear highly colorful headdresses as signs of their social status. This application would indicate that the color chart, containing in its full spectrum all possible colors, exposes a kind of totality that can also function socially as a mirror of power. However metaphorical that mirror may be, the color chart has remained a preoccupation of humankind since cultures became interested in understanding and codifying perception.

3) art > color theories > art as a perceptual paradigm > the color chart and the brushstroke-the dot-the pixel-the grid > Seurat, Delaunay, Boccioni, Mondrian, Albers

4) chemistry> molecular structure of pigments (ontology) > paint samples or how the color chart exists today in society at large-- as paint choices

In western painting, the decoding of what constitutes visual perception has informed a vast array of artistic productions. Mondrian tapped into that paradigm by focusing on what today we would call individual pixels of pure colors, sounding the presence of the all-powerful grid containing them. Bigger pixels, smaller pixels, black grids, colorful grids, all reductions of perception to its minimum units of light; a perfect structure that can synthesize the whole of visual perception: painting, an act that acknowledges its own intrinsic order. The totality of Mondrians' oeuvre: a logical investigation of the structural order of perception. If Mondrian, instead of being born in a small city in the Netherlands, had been born in some remote settlement in the Amazon, I imagine he would have been really interested in parrots. Probably, he would have made the greatest headdresses of all.

5) technology > proliferation of mechanical/electronic reproduction > the color pixel as the unit of representation

Nowadays the preoccupation with codes of perception has shifted to the production and fast proliferation of means of reproducibility--technology. Operations of de-codification seek to capture and reproduce the world as an image constituted by its reflection of the electromagnetic spectrum of light. Machines, acting as chameleon skins, scan the world in order to control it as an image. Such mastery deploys a grid that divides perception within the frame as if filtered through a tight mesh, allocating to each of the units in the structure a numeric ID, numbers that when added amount to a translation of the real out there into its visual resemblance here on the screen. The notion that everything in the world can be divided by a grid and reduced to pixels is a specifically contemporary condition of reproducibility. People go to museums and photograph artworks with their cell phone cameras and e-mail them to their friends. These random mirrorings through cheap, widely available means of reproduction, embody a tropism, one that mass culture is experiencing ad infinitum in its mimetic path towards parrotization.

At this point I should introduce the "parrotization of culture," a concept I devised in the fashion of Mikhail Bakhtin's notion of the "novelization of the culture." Bakhtin posits the overarching, open structure of the novel as one that contains all other forms of discourse. What I call the "parrotization of the culture" involves a paradigm shift. This shift accounts for the cultural impact of digital technology and its representational forms of codification, construction, repetition, mirroring, fragmentation and distribution. This spectacular alienating collage of the streets and the screens, a cacophony of echoes in which contemporary existence takes place affects us in ways that make us be … come more like parrots.

SYMBOLIC ROLE IN CULTURE

a) psychology> identification, color as signifier of subjectivity: gender, mood, inner self (artist’s palette), fashion >chromo-therapy, healing through color stimulation / colors in memory

The signifying applications of color in society are vast; they underwrite constructs like “essence” and “subjectivity,” providing a spectrum for identification in matters of race, gender, and ethnicity, among other things. At this intersection we find the rather complicated subject of pigments and choice.

In art, the most obvious case may be the role color choices play as signifiers of subjectivity in the painter's palette, a selection of pigments sometimes considered a mirror of the genius' individual soul. In fashion, the colors you wear on the outside reflect your mood because your appearance acts as the monitor of your inner self. You are what you wear.

Although many psychologists are dubious of the scientific relevance of chromo-therapy, it is widely practiced, with positive therapeutic results. Enveloped as fields of color, the stimulation by the pigmentation of light can indeed result in the cultivation of certain emotions or states of being. Nothing could be more illustrative of this fact than the public's response to the light installations of artist James Turrell.

Colors, like a madeleine teacake, can trigger a specific chain of associations and emotions based on memory. The colors of a certain season suddenly remembered open a window onto things we thought we had forgotten.

b) consumer culture > choice of colors = personal taste > marketing: implementation of color as identification> the culture industry, false choices

The public urban appearance of natural colors, the use of paint and dyes in objects, billboards, photography, and the ever-invasive realm of advertising all deploy mechanical reproduction in an interpellation and targeting of subjectivity that beg the question of choice amongst flavors.

If color is a matter of taste, then the colors of commodities would be a matter of intense speculation. Consumer culture manages a portfolio of people's chemistry like nothing else, for consumerism offers plenty of choices, except the choice of no consumption. The culture industry cheats consumers by delaying and endlessly deferring the delivery of gratification; the choices it offers are illusory. However, the question remains: what is the meaning behind color choices? If they are interchangeable, why is it that certain colors seem to be personally acceptable or socially appropriate and not others?

LANGUAGE / SPEECH

communication, mimicry, performance

PARROTS IN HISTORY

a) Delumeau > XVII century, the parrot was the witness of paradise

According to the renowned historian Jean Delumeau, in the European mind of the seventeenth century the parrot was the quintessential bird of paradise. That is because at the time people believed that in the Garden of Eden all animals could talk. And they did …until the original sin took place …when they lost their voices. Only the parrot retained the capacity of speech, and so it was that the parrot became the witness of creation, the voice of a lost world.

In this, the age of reason, earthly paradise became a topic of intense theorization. The Catholic world was polarized in theological speculation about Eden's chronology (what happened in the garden hour by hour) and its geographical location. With the Reformation the Vatican lost its influence over the half of Europe north of the Alps. Conveniently, the discovery of the new world presented a new myth of Paradise, a paradise found, and by extension, new frontiers for the expansion of the faith. People believed the world was less than four thousand years old. They also believed parrots could live up to six hundred years. It was thus deduced that some might still remember ….the lost language of Eden.

Here is a painting of Adam and Eve made by Titian and here is a replica of it made by Rubens. The only substantial difference between them is that Rubens inserts a red parrot into the painting as witness to the scene. This historical correction, the insertion of a species of parrot indigenous to Brazil, exhibits the impact of the discovery of the New World as a Paradise for the European imaginary.

b) Eco > the search for the perfect language “the tongue of Adam”> the common language spoken by god, humans and animals in the garden > the capacity of speech > matrix of all languages

As Umberto Eco has shown, throughout history there have been many attempts to recreate the language of Adam. The common language spoken by God, humans, and animals, the utopian lingua franca of the garden, indeed, predated the confusing cacophony of Babel. Today, we learn more languages than ever before. Whether we grasp the meaning of words may or not may be irrelevant. However, as a global trend, the mimetic impulse persists.

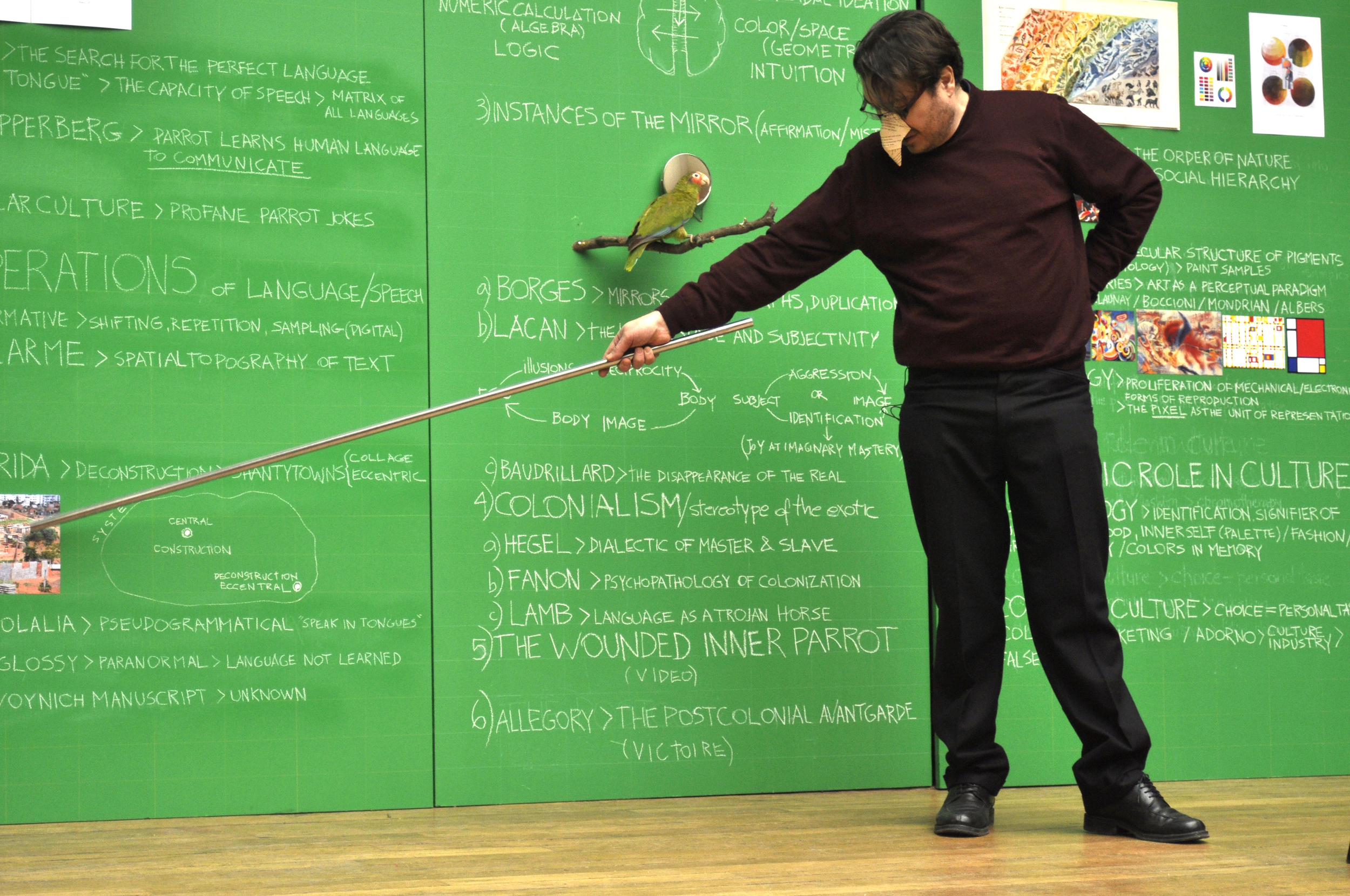

c) Dr. Pepperberg > parrots learn the use of human language to communicate

Scientific research on parrots took a dramatic turn when the experiments carried out by Dr. Pepperberg at Brandeis University determined with Alex (an African gray) that parrots can indeed learn to use human language to communicate. The study also demonstrated that Alex could even create new words by combining the sounds and meanings of others. In other words, parrots can create alternative languages based not merely on phonetic resemblance but on an understanding of the meaning of the sound, as it is codified in language: a deviationist path, a kind of "parrot slang," if you will.

d) popular culture > profane parrot jokes

This is a topic that probably everybody has experienced at some point. The presupposition of these jokes is that the parrot knows what it says.

OPERATIONS OF LANGUAGE

1) performative language by mirroring > shifting, repetition, sampling, digital technology

Parrot talk is more than repetition. It is a collage-like, cut-and-paste-performance with language based on a mimetic impulse, a kind of empathic interaction that resembles its surroundings. Parrots often imitate the sounds of other birds and animals, even sounds made by objects. Yet the time sequence in which sounds emit from their beaks belies a kind of shuffle, a sampling of chance. This is not Joyce's stream of consciousness but a path of shifting terrains. Sampling is like micro repetition, an operation that can select a syllable, repeating it as is or altering it, stretching it, or compressing it in time. Digital technology has expanded on the potential applications and mirroring mechanisms of “parrot talk”.

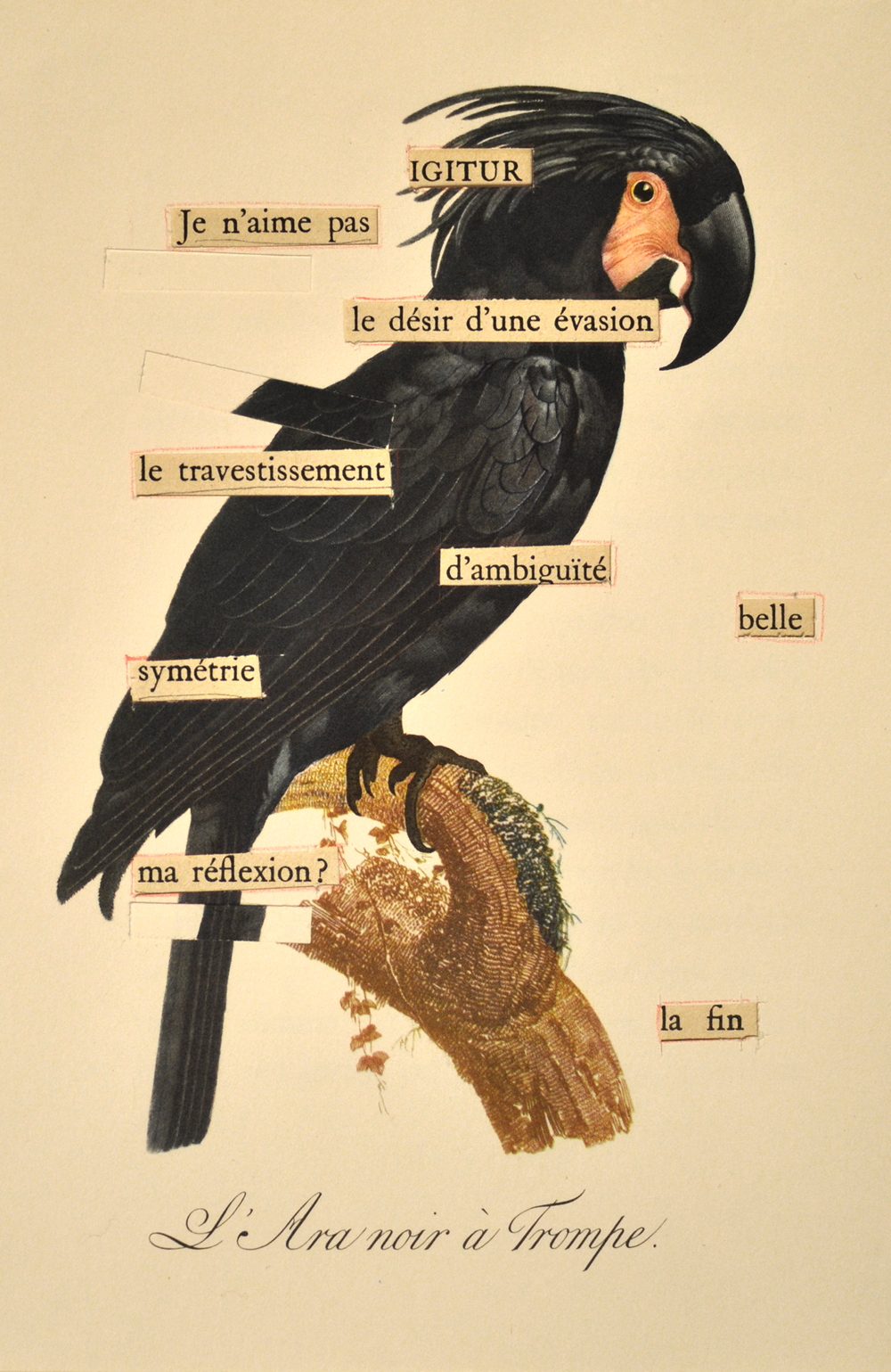

2) Mallarmé > mirrors and the spatial topography of language

According to Zachmann, Mallarmé's Igitur analyzes the place of the mirror and the specular functions of both consciousness and art. It addresses the mystery of literature as a problem linked to a phenomenology of perception and to the ontological conditions of language, that is, the materiality of words and their signifying operations.

Mallarmé's poetry dismantles the linear progression of the text, replacing it with an almost tactile topographical, fractal structure that places words as they may indefinitely occur in the space of experience, structurally deployed in the spatial frame of the page. This operation of shifting terrains, surprising in its deployment, posits a poesis in sync with the time of sensorial perception and inner experience. The page operates as a mirror for the artist’s becoming, but also for the reader’s; they both meet in the folds of multiple writings, bringing their selves into the site of the text.

Parrots too are known for their capricious use of language. If we were to transcribe their speech it would probably resemble some of Mallarmé's pages in Un Coup de dés. The fragmented order of parrot talk is a transgression of narrative, because narrative relies on the linear thread of the story. Speech becomes a time collage. For us the surprise lies in the impression that the parrot meant what it said, a kind of reflex we have to ascribe meaning to signifiers. The parrot's colorful words come into the present like a wind and blow away the names we had given to things.

And yet, parrots may not just repeat. For they can learn the meaning of words and pronounce them with the original intonation in which they heard them for the first time. Individual forms of speech often mimic the way other people spoke in that person's infancy. When we mirror our parents, our subjective experience is matched with an exterior resemblance, a simulacrum akin to the materiality of the text.

3) Derrida > deconstruction > presence is always divided > shanty towns, the eccentric location

Deconstruction is not merely a set of theses that we remove from one context to apply to another, although we do that all the time. Deconstruction exists in its applications as shanty towns exist in the context of the city—eccentrically. Their formation can be interpreted as resulting from the city's hegemonic centralized construction as a totalizing entity. Shanty towns come into being as a deconstruction of the city in the most literal sense; these precarious, informal dwellings are erected from recycled materials discarded by the city and its industries. The parrot's deconstruction of language, an assemblage of empathy and mimesis, resembles that of the shanty town’s construction, for the façades of the city’s shanty towns (a collage based on the necessity of function) randomly display the material fragments of the city’s own deconstruction.

4) glossolalia > pseudo-grammatical, speech without intent of communication, fluent speech-like unintelligible utterances > Pentecostal “speaking in tongues”, a gift of the Holy Spirit > Flaubert?

5) xenoglossia > paranormal > to speak a language not learned

6) the Voynich manuscript

Among the mysteries of speech's promiscuous relationships with language, glossolalia is one of most peculiar attributes. When pentecostals go into those hoola-magula rants called "speaking in tongues," it is supposed to be a gift to them coming straight from the Holy Spirit. Although in truth parrot talk is more interesting than this, could it be that in Un Coeur simple, Flaubert's character Félicité was correct in her assumption that her parrot was indeed the Holy Ghost?

Xenoglossia is the de facto acquisition of a language. It is as if an inner switch gets randomly turned on. Ian Stevenson, a Canadian psychiatrist at the University of Virginia, working on paranormal phenomena, has supposedly found verifiable confirmations of true cases of xenoglossia.

The Voynich manuscript presents a puzzling mystery. A supposedly European text dating from somewhere between the thirteenth and seventeenth centuries, the illustrated manuscript has not yet been deciphered by any cryptologist. It presents an ostensibly intelligible, yet still unknown language that seems to contain highly developed scientific knowledge.

MIRROR

Flaubert > the parrot as the Holy Spirit > the sacred = the profane

Flaubert's short story brings us to the functions of the parrot as a mirror: In this case, a mirror of the soul of divinity, an instance of purity that contradicts profane interpretations of parrots.

THE HUMAN BRAIN

Corpus callosum > the site of translation

cross over = translation

This is a somewhat outdated version of the location of functions in the brain. However, it is employed in this context as a metaphorical axis. The cerebral cortex is divided into two hemispheres. The left manages language, numeric formulations like algebra, and logic.The right manages color and spatial representations, non-verbal ideation, geometry, and intuition. Between them is the corpus callosum, an extensive set of connecting cables. It is in passing through this very part of the brain that impulses are translated. Crossing over one way, sensorial data becomes language, number, or logical thought; in the other direction, thought becomes intuition, space, and sensorial representation.

INSTANCES OF THE MIRROR

(affirmation or mistrust)

Borges > mirrors, photographs, duplication

Lacan > the mirror stage and subjectivity

A passage of Borges declares his profound distrust for mirrors and photographs because of their duplication of reality. Indeed mirrors and photographs exist in a state of duplicity and are often considered suspect. Explaining the mirror stage, Lacan propses that the visual identity given by the mirror supplies imaginary wholeness to the experience of a fragmented real. As a result of this split between image and experience, subjectivity finds itself caught, fraught in a libidinal relationship with its own image.

Baudrilliard > the disappearance of the Real

Baudrilliard said that to simulate is to feign what one hasn't. However, someone who simulates an illness can produce actual symptoms, destabilizing the distinctions between fact and fiction. As a result, the simulator cannot be treated, objectively speaking, as ill or not ill. In this scenario of possibilities Baudrillard deploys his theorization of the phases of the image.

PHASES OF THE IMAGE

1) it is the reflection of a basic reality

2) it masks and perverts a basic reality

3) it masks the absence of a basic reality

4) it bears no relation to any reality (it is its own simulation)

COLONIALISM

The parrot as stereotype of the exotic

To this commonly understood cultural stereotype, I would like to add that the parrot is exotic not just for its tropical origin, but also for its eccentricity, its difference and its differance. Something of its behavior makes it a mirror and a simulator, both a teaser and a source of empathy. I would even argue that these attributes of duplicity inform how the concept of the exotic rests on the construction of otherness as an image of desire operating within a frame of narcissistic impulses.

Parrot “dialogue”

Hegel > dialectic of master & slave

Fanon > the psychopathology of colonization

Lamb> use of art as a trojan horse

Expanding on Hegel's master-slave dialectic, Fanon argues that the colonizer fails to see its narcissistic reflection in the colonized. The broken mirror, an instance of misrecognition where the reflected image is rejected, has metaphysical implications for the colonizer and pragmatic ones for the colonized. The latter will indeed “mirror” the image of the colonizer, parroting the language of the master as a Trojan Horse.

THE WOUNDED INNER PARROT

We all behave like parrots. At one point or another we repeat things we heard somewhere and don't really know what we are talking about. Often, we say what we don't really mean. We copy the world around us and turn it into our own habits. We talk all the time, emitting from our mouths who knows what, we photograph, we text messages, we repeat. We assert our subjectivity through the empirical reshuffle of readymade signifiers and claim originality. Our thoughts come out as a collage. Our speech becomes a cacophony of barely comprehensible utterances. These actions do not reflect the idealized self-image we struggle to sustain. However, these operations do seem to reflect the conditions of our fragmented self. In truth we have not been fair to the parrot that lives inside of us! This is a wounded parrot, neglected and ostracized like a distant relative from whom we would rather not hear. That silenced, wounded inner parrot has a voice, a voice, a voice that we need to hear once again. Now I am going to show you how that parrot inside of us really feels.

(Video of crying parrot)

ALLEGORY OF THE POSTCOLONIAL AVANT-GARDE

The avant-garde has been the motor of change and renewal for art of the twentieth century. However, these movements predominantly concerned strictly localized revolutions of ideas in relation to their own self-involved artistic contexts. In addition, generational struggles over aesthetic conceptions were most often predicated on redefining what art is. We see the whole artistic enterprise of the last century fuelled by that promise. Today we don't really care about what art is or what it is not. Art's ontological status can no longer lead to any transcendental value judgment based on its intrinsic properties alone. Our preoccupation is not with what art is or is not, but with what art does in the real world. Whether this function of art in society is carried out through the mere investment of user values in aesthetic practices remains to be seen.

Nowadays, given the proliferation and availability of forms of reproducibility, and of information circulating through virtual global circuits, the map of colonialism is being reshaped from the inside out. Cultural hegemony and isolationism are privileges of the past. Think of the eagle, the all-powerful predator that sees everything from above. The image of empire and knowledge is suddenly turning into a pathetic creature. Who wants to be like an eagle, alone on top of a cold mountain eating one of its own kind? Eagles are finally seen for what they have always been: pale lonely cannibals on the path to extinction!

Meanwhile, parrots, like flocks of immigrants from the warm regions of the world, are crossing borders with their spices and colors. Because of global warming they are emigrating north. These parrots have a good life, eat the most delicious fruits and nuts and have no predators. In addition, they are communal, communicative, and have a great propensity to learn from others. With the “parrotization of culture”

information is no longer the privilege of the few. Society's tropism aims at the expansion of common knowledge. We are in the era of reproducibility and communications and everybody wants some airtime. We are all suddenly endowed with the power to reproduce the world around us and to talk about it, to make sense of it amongst ourselves. The masses that were kept silent for ages are beginning to chat. They are the voice of a global postcolonial avant-garde that is changing the shape of culture everywhere.

Today I want to propose that we finally engage with the parrot that we all have inside. Let's set it free. Let's give it a voice. Let us stretch our arms like open wings so those pure colors can shine under the sun once again. Let's celebrate together, declaring that the days of the eagle are indeed over, and the era of the parrot has begun!

(Disclosure of La Victoire Postcoloniale)

About Parrot Theory

My Aunt Hortensia had a parrot. She used to feed the bird with bread soaked in wine to promote its speech. It was a yellow-headed Amazon that barely had any feathers in its tail and it always seemed to be sick, most probably from a hangover provoked by alcohol intoxication steadily induced by its diet. When my uncle laughed, the parrot would laugh just as he did. After my uncle died, my aunt became very religious and would organize gatherings of churchgoers to pray at her house. A young couple from Paraguay had recently moved in next door. They had a stormy relationship, evidenced by constant, loud swearing, yelling, and rather harsh characterizations of each other. I remember hearing them. In the afternoons, my aunt would take the parrot to the peach tree in the back of the house. The bird had plenty of time to become acquainted with the neighbors. One day, Aunt Hortensia told my mother she was very upset by the parrot's behavior. It seems that during the churchgoer’s gatherings, the parrot would become talkative, combining prayers with curses, yelling, and outbursts of laughter. My mother advised her to end the bread and wine diet at once.

Perhaps it is because I saw the seed of a Dadaist in its attitude, an unapologetic irreverence for the established rules of society, that I became interested in the parrot and its dramatic potential as the main character of a story.

One late afternoon in the winter of 2002, I was walking along the cliffs of Chapada do Guimarães, carrying a backpack loaded with an arsenal of heavy photographic equipment. Startled by a cacophony coming from behind, I turned to see a flock of splendid red and green macaws flying at a distance. As I came into a clearing in the forest, the parrots returned. After circling over my head, they landed on the branches of a small, dead tree in front of me. I was perplexed. No other bird would do that. It was obvious that they came down to check me out. I very slowly put down the backpack and tried to retrieve my camera but the parrots started talking:

Crawwhhh, Wrackh, Araaara, ARARA, Crawwhhh, wrhaaahck, crawhhh...

Some of them stared, looking me straight in the eye. They started taking turns, voicing what they had to say. These parrots are really loud, yet at points they would look at each other and talk in a lower pitch as if commenting on me, moving their heads back and forth in agreement. When I finally pulled out my camera and was ready to photograph them they became quiet. At that moment, which seemed unusually long (like those before an accident), they gave me a last glance and flew away in silence, all of them, at once. Not long after, on my way back, they passed over me again with a Craaaaawwhhh, Araaaara, crawhhh… Ararararahhhrahhh Arraaaaaaaraaaarah, craaaawwwwhh… arrraaaarahh… I thought they were acknowledging our previous meeting; it felt like a salute, as when a neighbor says hi from across the street.

What interests me about parrots is not just how they are like us, but how much we are like them. They make me suspicious of our original ways of being human and of our perpetual desires for mimetic representation, translation, and referentiality. I began to observe people's behavior in the streets, in shops, restaurants, and airports. We are constantly involved in our own ways of representing and signifying the world around us, a world of mirrors. How much we talk, even when we have nothing to say!

I was coming back from Mato Grosso on a stormy afternoon. As I sat in the boarding area of the Cuiaba airport, deep orange rays of sun suddenly burst through the clouds. Ablaze, my eyes mirrored the fiery sky. And in this purifying spectacle of light, my gaze dissolved …into pure color. I had a vision. We are increasingly becoming more like, more like, more like… parrots! Our contemporary condition of existence is one of a sweeping and brilliant tropism. A paradigm shift: society, culture and the material world are engaged, ad infinitum, in a path towards parrotization.

Parrot Theory is a multimedia exhibition that focuses on intertextuality: the play between language, reproducibility, and color that informs various interpretations of parrots in culture. Parrots signify eccentricity for their unpredictable behavior, and for their idiosyncratic, ambiguous presence as destabilizing mirrors of language and visuality. Parrots also embody a paradigmatic case of pigmentation; their plumage contains the most complete gamma of colors of the natural world.

Parrot Theory displays an assemblage of ready-made representations of parrots disclosing the multiple roles that parrots occupy in popular narratives. Flagrantly figuring the exotic and the tropical, the parrot also alternatively embodies the confidant, the eccentric, the toy, the phallus, the Holy Spirit, the mirror, the tease, and the souvenir.

The video, "Genesis According to Parrots" (2005), filmed in Mato Grosso, Brazil, casts parrots as the quintessential witnesses of Paradise. Testifying and mischievously retelling the story of the Genesis, the parrot panel discussion draws parallels between the discourses of creationism and colonialism, provocatively exposing the colonizer as creator.

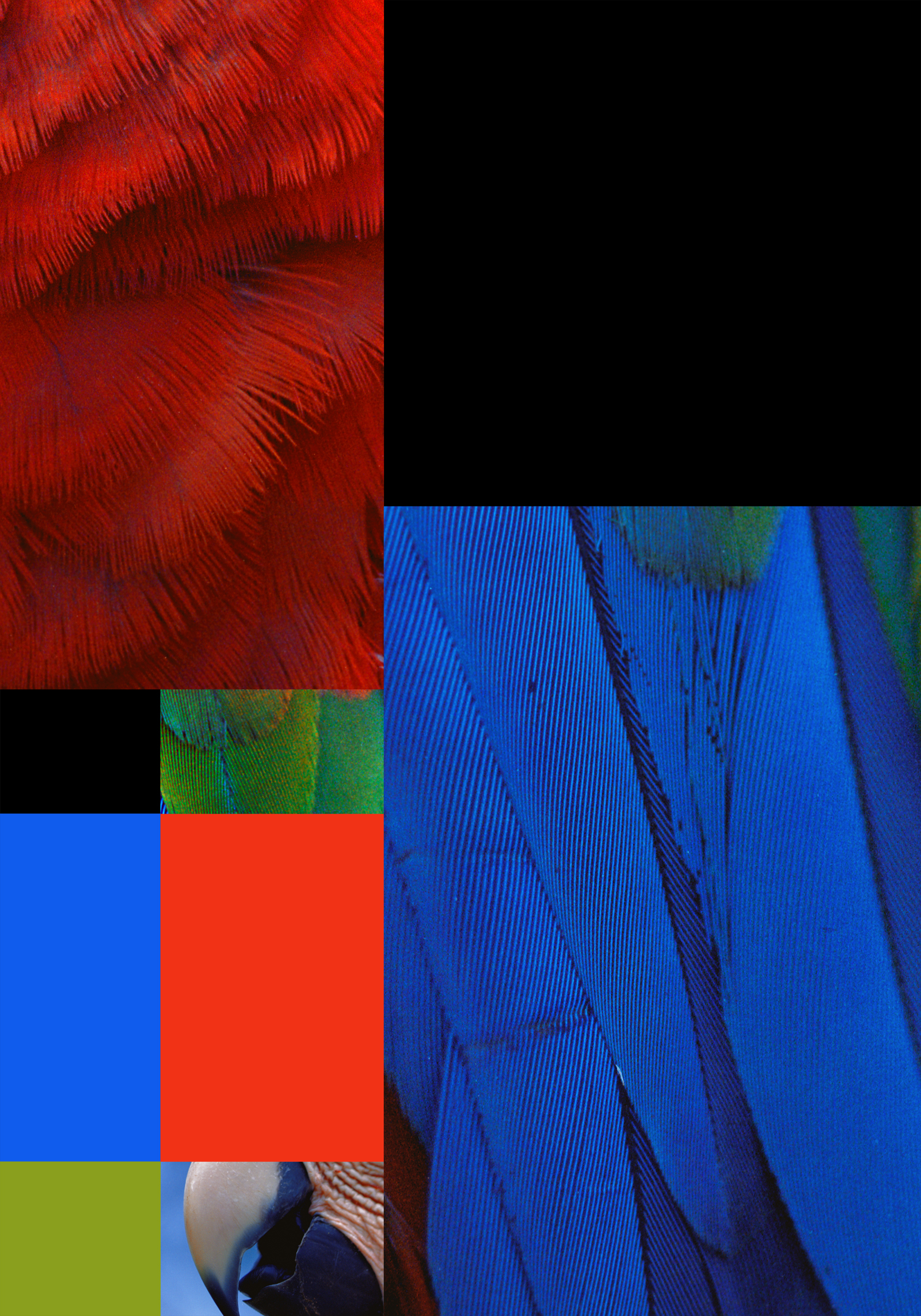

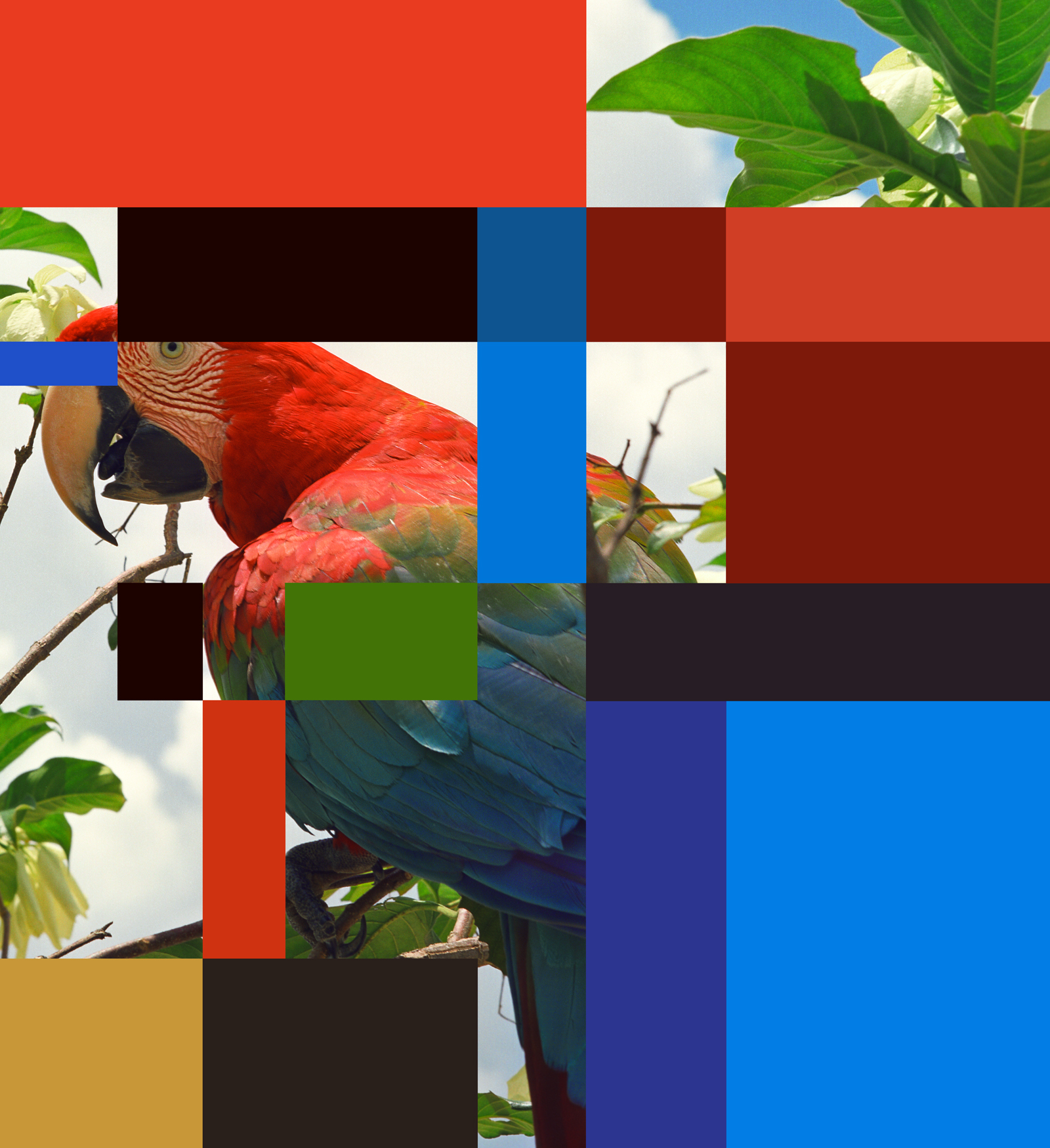

The "Parrot Color Chart" series explores the photographic image as an archive of color. These lush photographs capture parrots in the idealized settings of a baroque, vulgar naturalism. The series zooms into color, sampling individual pixels from the photograph and reproducing them in a larger grid, one that exceeds the boundaries of the image. In these "indexical paintings," the photograph mirrors and repeats itself, exposing a mise en abyme of random, structures. The parroting strategies proliferate in kaleidoscopic compositions of nature that take modernist aesthetics on a detour into a Dionysian realm of Edenic fantasies.

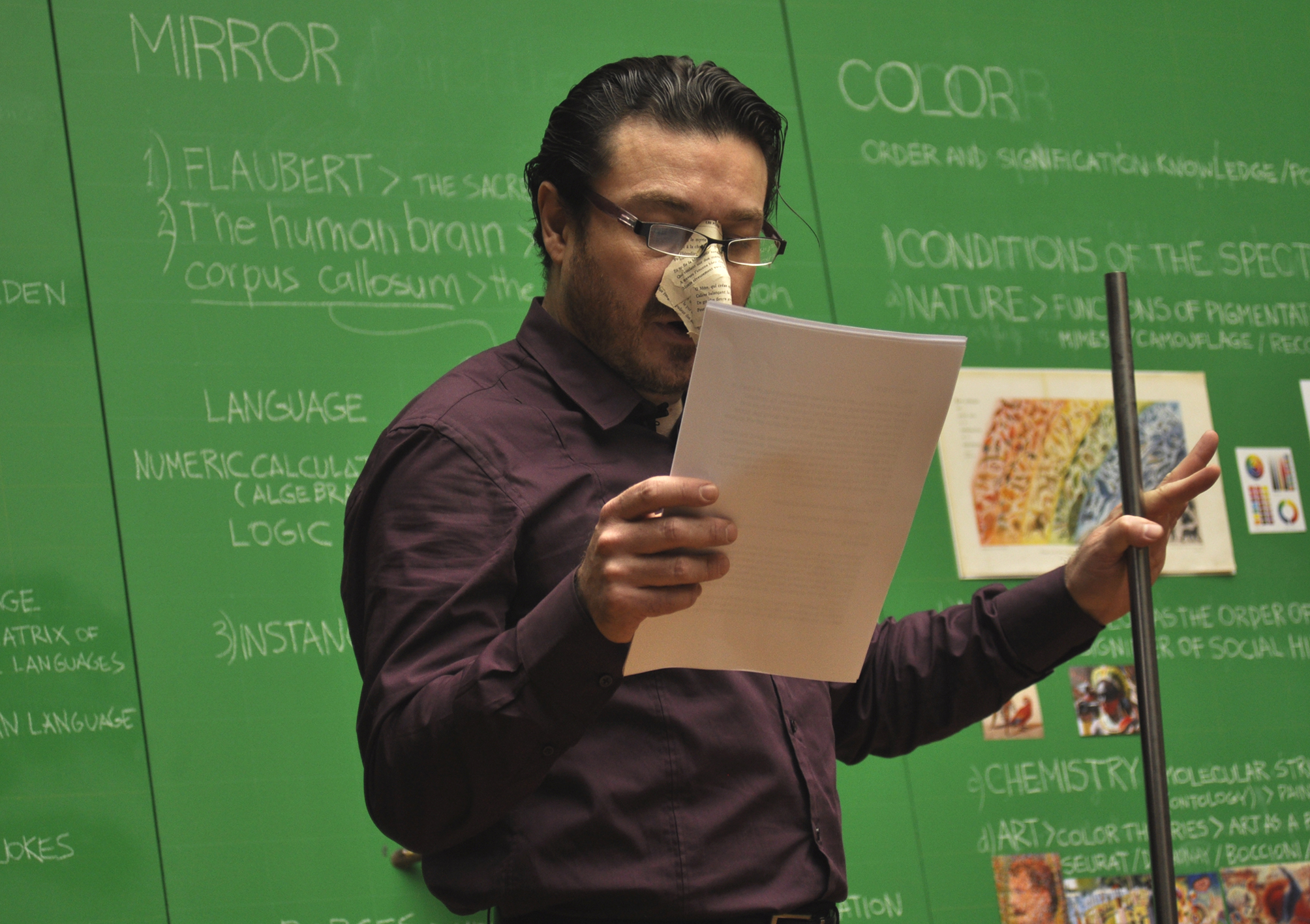

"Parrot Theory 101" is a performance that simulates a lesson, mirroring academic settings, language, and methodologies. Disclosing the symptoms of theoretical argumentation, it cannot be treated realistically as theory or not theory. This specific form of duplicity opens a dialogue on the "parrotization of culture," analyzing how culture asserts itself through its own duplication. The “parrotization of culture” is best understood when experienced as a mimetic tropism of culture at large, a phenomenon that can be ascribed to the rapid proliferation of cheap forms of reproducibility; to the cultural impact of digital technology and its representational forms of codification, construction, repetition, mirroring, fragmentation and distribution; to the endemic cyclical repetitions in private, public, and academic discourses; and to the perennial return of the fashionability of color. Rising from the ashes of the eagle, a rather uninteresting signifier after all, the parrot becomes an illuminating allegory: the rise of a global, postcolonial avant-garde forever changing the world into words, mirrors, and colors, as we speak…

Sergio Vega

Paris, March 7, 2009